5/30/2006

5/27/2006

Meg

I guess this is the link for the movie, or at least for someone whose trying to sell the book, or something...I don't know, I'm no good at reading! But they don't have this image on that site, only some lame photoshopped ones.

We've seen tons of shark movies, the worser the better. Maybe we'll post some reviews someday. It would be tough to outdo this site:

"Through the poor filmmaking and ridiculous storyline, we are left with a pretty good shark performance. [?] This is based solely on the films complete use of real tiger sharks. There are no mechanical or computer generated fish to be seen. While this is intriguing, it in no way makes it a better film. I don't know if it scientifically accurate, but this shark rarely breaks water. We are never treated to a shark fin, a staple of the genre."

Katie read the book "Meg" (of course) and the only thing I remember her saying about it was that the Megalodon survived for all those years in a deep sea volcanic trench, and it was able to climb out into colder water by staying warm in the blood of another Megalodon it was eating...or something!

Here's another picture I found on the World Wide Web.

We saw this movie a while back and enjoyed it a lot. It has bad special effects, story, acting, etc. but a shark eats an entire yacht in one gulp. I think it also eats a helicopter. Here it is eating a motorboat.

5/24/2006

5/23/2006

Zadie Smith

The critic James Wood appeared in this paper last Saturday aiming a hefty, well-timed kick at what he called "hysterical realism". It is a painfully accurate term for the sort of overblown, manic prose to be found in novels like my own White Teeth and a few others he was sweet enough to mention. These are hysterical times; any novel that aims at hysteria will now be effortlessly outstripped - this was Wood's point, and I'm with him on it.-from here, way back in 2001.

[...]It's all laughter in the dark - the title of a Nabokov novel and still the best term for the kind of writing I aspire to: not a division of head and heart, but the useful employment of both. And I could mention dozens of novels (I haven't been writing, but boy, I've been reading) that create a light in my head in between the news bulletins. Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich - a miniaturist tale of a bourgeois man dying a bourgeois death - every time I read it, I find my world put under an intense, unforgiving microscope. But how does it work? I want to dismantle it as if it were a clock, as if it had parts, mechanisms. I wonder if Wood will take that question, then, as a replacement for my earlier one. Not: how does this world work? But: how is this book made? How can I do this?

But he might see even that question as too intellectual in approach. I think Wood is hinting at an older idea that runs from Plato to the boys booming a car stereo outside my freaking window: soul is soul. It cannot be manufactured or schematised. It cannot be dragged kicking and screaming through improbable plots. It cannot be summoned by a fact or dismissed by a cliché. These are the famous claims made for "soul" and they lead with specious directness to an ancient wrestling match, invoked by Wood: the inviolability of "soul" versus the evils of self-consciousness and wise-assery, otherwise known as sophism.

Well, it's a familiar opposition, but it's not very helpful (it's also a belief Oprah shares, and you want to be careful which beliefs you share with Oprah). I wonder sometimes whether critics shouldn't be more like teachers, giving a gold star or a black cross, but either way accompanied by some kind of useful advice. Be more human? I sit in front of my white screen and I'm not sure what to do with that one. Are jokes inhuman? Are footnotes? Long words? Technical terms? Intellectual allusions? If I put some kids in, will that help?

Catastrophe

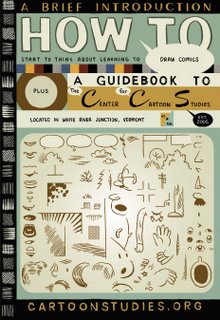

Meanwhile thanks for stopping by everyone who followed the link over at comicsreporter.com. Now go outside, take a walk or something, it's springtime!

Update: It's back up again.

5/19/2006

Id, Ego, etc.

Seth: You had a period, like with the underground cartoonists, where they went through the whole taboo-breaking phase, and also attempting to show that comics could cover a wide range of material. But nobody really had any concrete literary aspirations. I think it took a little while, even in the the first part of the early '80s for cartoonists to come around to the idea that perhaps longer stories and more challenging content was acceptable. But it seems like it's the next step. As comics move forward, that's really the areas that can be pursued; not coming up with new gimmicks or clever characters, or not finding flashier ways to tell the story so much, as to try and actually infuse it with some content.

GG: That generally sounds like a pretty accurate historical assessment.

Seth: Although I'm a little worried at the moment. I really felt a couple of years ago that this was obvious to everyone working in the alternative market. But I've felt in the last couple of years that there's a bit of a swing back with the next generation of cartoonists toward this concept of "Fuck this boring shit! Comics are supposed to be fun!" Sort of a return to this idea that you don't want to get overly pretentious. Maybe it's a bit of a reaction to all of this autobiography.

-from an interview in the Comics Journal #193

Feb. 1997

5/15/2006

5/10/2006

5/07/2006

And compare that Richard Powers quote with this (from here).

Wood's use of "smartness" there is a signal that he's referring to what Zadie Smith has said somewhere about how she's impressed by David Foster Wallace and writers of his ilk (Wood calls them "hysterical realists") being so "smart." Wood likes Smith best of the "hysterical realists," as far as I can tell.At present, contemporary novelists are increasingly eager to "tell us about the culture," to fill their books with the latest report on "how we live now." Information is the new character; we are constantly being told that we should be impressed by how much writers know. What they should know, and how they came to know it, seems less important, alas, than that they simply know it. The idea that what one knows might – to use Nietzsche's phrase – "come out of one's own burning" rather than free and flameless from Google, seems at present alien. The danger is that the American fondness for realism combines with this will-to-information to produce a hyperliteralism of the novel: you can see this in Tom Wolfe....

By "hysterical realism" I have meant a zany overexcitement, a fear of silence and stillness, a tendency toward self-conscious riffs, easy ironies, puerility, and above all the exaggeration of the vitality of fictional characters into cartoonishness. The dilemma could be put dialectically: the writer, fearful that her characters are not "alive" enough, overdoes the liveliness and goes on a vitality spress; suddenly aware that she has overdone it, she tries to solve the problem by drawing self-conscious attention to the exaggeration...But the self-consciousness, far from healing the wound, merely makes it bloodier.[...]

My second critical preoccupation flows from the first: there is a generalized overemphasis on a certain kind of intelligence in fiction – now habitually and tellingly renamed "smartness." We are now so convinced of the terrifying complexity of our culture that we tend to flatter those writers who grapple with it at all, certain that they must be very brilliant just to be attempting it. But Proust rightly said in Contre Sainte-Beuve that to say of a novelist "he is very intelligent" is no different from saying "he loved his mother very much."

-James Wood

"Reply to the Editors,"

n+1 #3

Sort of related--I just finished DFW's book on infinity and math Everything and More.

5/05/2006

RP: That's just it; the economics of higher education now prevent the kind of interdisciplinary vision that I'm describing. I think that a literary critic's work would only be enhanced by a more sophisticated sense of, say, evolutionary paleontology, or molecular biology, or cognitive science, or cosmology. We want to be able to ask answerable questions, but we also want to be able to situate those answers in a broader geography, an engagement of the larger human questions. And that's how my books work; they work by saying you cannot understand a person minimally, you cannot understand a person simply as a function of his inability to get along with his wife, you cannot even understand a person through his supposedly causal psychological profile. You can't understand a person completely in any sense, unless that sense takes into consideration all of the contexts that that person inhabits. And a person at the end of the second millennium inhabits more contexts than any specialized discipline can easily name. We are shaped by runaway technology, by the apotheosis of business and markets, by sciences that occasionally seem on the verge of completing themselves or collapsing under its own runaway success. This is the world we live in. If you think of the novel as a supreme connection machine -- the most complex artifact of networking that we've ever developed -- then you have to ask how a novelist would dare leave out 95% of the picture.