You are reading "the Balloonist" to find out more about balloons, so let's take a look at Thierry Smolderen's fascinating article in the wonderful new Comic Art Magazine, in which he makes some claims about the development of the word balloon.

He asks: why did it take so long for someone to put together a sequence of pictures that tell a story and word balloons that show what the characters are saying? It wasn't until Opper, Outcault, Swinnerton in the 1890s that the formal arrangement of elements that make up what we recognize as comics really caught on.

I remember back in college writing papers for my Aesthetics class about the formal elements of comics (boy, I was spending my money well! and come to think of it, I'm still paying off those loans), trying to puzzle out a definition of comics, which seemed important at the time, due to the influence of "Understanding Comics" on me in high school. What was so puzzling was that if I came up with a definition, say, something like "words and pictures in sequence," I kept finding so many other things that fit the definition which were clearly not comics. It was absurd, I thought, to think a gallery exhibition, a magazine article, or a cereal box all fit the formal definition of comics. But then after reading Nelson Goodman (via WJT Mitchell) I came to see that what was important wasn't so much the marks on the paper, it was how you read them. It's embarrassing to admit, but I remember my mind being blown by the realization that what we call "comics" wasn't best defined as a form, but as part of an ongoing historical process, the messy forces of culture and commerce driving image-text combos to evolve into a particular species of art form, which is still evolving. At the time I knew very little about biology, but now I see how the development of comics resembles the inelegant trial and error and "act of God" forces at work in biological evolution. Or maybe comics is something more like the development of an ecosystem?

pictures in sequence," I kept finding so many other things that fit the definition which were clearly not comics. It was absurd, I thought, to think a gallery exhibition, a magazine article, or a cereal box all fit the formal definition of comics. But then after reading Nelson Goodman (via WJT Mitchell) I came to see that what was important wasn't so much the marks on the paper, it was how you read them. It's embarrassing to admit, but I remember my mind being blown by the realization that what we call "comics" wasn't best defined as a form, but as part of an ongoing historical process, the messy forces of culture and commerce driving image-text combos to evolve into a particular species of art form, which is still evolving. At the time I knew very little about biology, but now I see how the development of comics resembles the inelegant trial and error and "act of God" forces at work in biological evolution. Or maybe comics is something more like the development of an ecosystem?

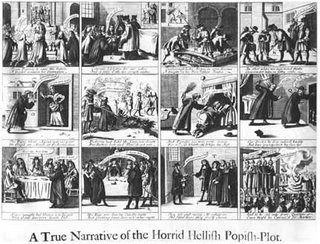

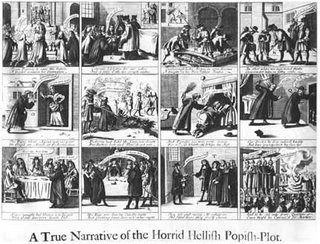

Anyways the reason I'm bringing this is because it relates to Smolderen's discussion of "A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot."

Not a Chick tract, this is reprinted in David Kunzle's The Early Comic Strip (1973), which I was lucky to have in my college's library, along with Kunzle's other awesome "History of the Comic Strip: Vol. 1: The Early Comic Strip: Picture Stories & Narrative Strips in the European Broadsheet , ca.1450-1826". In the article, Smolderen takes issue with Kunzle calling this a proto-comic strip.

We want to avoid a creative anachronistic comics history, the kind that used to get Eddie Campbell so mad at Scott McCloud's indescretions, and the kind that puzzled me when I was trying to come up with a formal definition. The narrative sequencing of image units we read in modern comics is a relatively late development in cartooning. Before this, "proto-cartoonists" drew in a different context of reading and image-making, a tradition going back Baroque craze for making emblems or thematic drawings. The drawing-plus-text wasn't to be read as a narrative scene, but as a statement about the subject of the drawing. The "word balloons" that float alongside the figures like ribbons amplified the thematic reading -- the drawing "spoke" about itself for the reader. The character was not "speaking" in a narrative sequence. Smolderen shows that the content of the word balloons almost always should be read in this way.

The development of the modern word balloon, which is one of the main organs of what makes comics comics, developed in the 1890s. Opper started using word balloons in the late 1800s in the way we read them today -- as encircling words that represent speech by characters in an narrative space. Man, I'd love a big collection of Opper, wouldn't you? Smolderen in the essay traces how Opper eventually turned speech balloons into representations of "speech acts," as we read them today, by putting them in the context of slapstick action sequences. Hard to believe it took so long for this to get put together! Seems obvious to me.

I've only gone through some of the article here. There's also fascinating stuff about how Topffer's version of comics was different than what we have today, as well as a revelatory discussion where he traces the development of modern word balloons to the problem of how to represent parrots, Edison's phonograph, and cheap printing technology in cartoons, and more.

He asks: why did it take so long for someone to put together a sequence of pictures that tell a story and word balloons that show what the characters are saying? It wasn't until Opper, Outcault, Swinnerton in the 1890s that the formal arrangement of elements that make up what we recognize as comics really caught on.

I remember back in college writing papers for my Aesthetics class about the formal elements of comics (boy, I was spending my money well! and come to think of it, I'm still paying off those loans), trying to puzzle out a definition of comics, which seemed important at the time, due to the influence of "Understanding Comics" on me in high school. What was so puzzling was that if I came up with a definition, say, something like "words and

pictures in sequence," I kept finding so many other things that fit the definition which were clearly not comics. It was absurd, I thought, to think a gallery exhibition, a magazine article, or a cereal box all fit the formal definition of comics. But then after reading Nelson Goodman (via WJT Mitchell) I came to see that what was important wasn't so much the marks on the paper, it was how you read them. It's embarrassing to admit, but I remember my mind being blown by the realization that what we call "comics" wasn't best defined as a form, but as part of an ongoing historical process, the messy forces of culture and commerce driving image-text combos to evolve into a particular species of art form, which is still evolving. At the time I knew very little about biology, but now I see how the development of comics resembles the inelegant trial and error and "act of God" forces at work in biological evolution. Or maybe comics is something more like the development of an ecosystem?

pictures in sequence," I kept finding so many other things that fit the definition which were clearly not comics. It was absurd, I thought, to think a gallery exhibition, a magazine article, or a cereal box all fit the formal definition of comics. But then after reading Nelson Goodman (via WJT Mitchell) I came to see that what was important wasn't so much the marks on the paper, it was how you read them. It's embarrassing to admit, but I remember my mind being blown by the realization that what we call "comics" wasn't best defined as a form, but as part of an ongoing historical process, the messy forces of culture and commerce driving image-text combos to evolve into a particular species of art form, which is still evolving. At the time I knew very little about biology, but now I see how the development of comics resembles the inelegant trial and error and "act of God" forces at work in biological evolution. Or maybe comics is something more like the development of an ecosystem?Anyways the reason I'm bringing this is because it relates to Smolderen's discussion of "A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot."

Not a Chick tract, this is reprinted in David Kunzle's The Early Comic Strip (1973), which I was lucky to have in my college's library, along with Kunzle's other awesome "History of the Comic Strip: Vol. 1: The Early Comic Strip: Picture Stories & Narrative Strips in the European Broadsheet , ca.1450-1826". In the article, Smolderen takes issue with Kunzle calling this a proto-comic strip.

"[the print] does not imitate the continuous flow of topical events so much as it arrests the progress in a series of "stations" functioning as isolated, diagrammatic allegories...the labels [proto word balloons] inhabit an abstract hieroglyphic space generally incompatible with a dynamic narrative...the captions, not the labels, are leading the tale."

We want to avoid a creative anachronistic comics history, the kind that used to get Eddie Campbell so mad at Scott McCloud's indescretions, and the kind that puzzled me when I was trying to come up with a formal definition. The narrative sequencing of image units we read in modern comics is a relatively late development in cartooning. Before this, "proto-cartoonists" drew in a different context of reading and image-making, a tradition going back Baroque craze for making emblems or thematic drawings. The drawing-plus-text wasn't to be read as a narrative scene, but as a statement about the subject of the drawing. The "word balloons" that float alongside the figures like ribbons amplified the thematic reading -- the drawing "spoke" about itself for the reader. The character was not "speaking" in a narrative sequence. Smolderen shows that the content of the word balloons almost always should be read in this way.

The development of the modern word balloon, which is one of the main organs of what makes comics comics, developed in the 1890s. Opper started using word balloons in the late 1800s in the way we read them today -- as encircling words that represent speech by characters in an narrative space. Man, I'd love a big collection of Opper, wouldn't you? Smolderen in the essay traces how Opper eventually turned speech balloons into representations of "speech acts," as we read them today, by putting them in the context of slapstick action sequences. Hard to believe it took so long for this to get put together! Seems obvious to me.

I've only gone through some of the article here. There's also fascinating stuff about how Topffer's version of comics was different than what we have today, as well as a revelatory discussion where he traces the development of modern word balloons to the problem of how to represent parrots, Edison's phonograph, and cheap printing technology in cartoons, and more.

2 comments:

Looked in on one of my curiosity-jaunts through the blogosphere. enjoyed your post. Re McCloud. It always seemed illogical to me to define comics and then call everything that fit that definition 'a comic'. It struck me as more logical to conclude that because so much disparate stuff could be seen to fit then obviously these techniques cannot be unique to comics, and therefore comics is but one manifestation, out of many, of an urge to make sequential images. Whether that means we belong to a much smaller historical stream or are the latest manifestation of a universal tendency all depends on how you want to look at it. I'm also suspicious of a view of history that regards our predecessors as preparing the way for us, as though we were the Graet Coming, and as though they cared a shit about us. We all know that the oldies would see us a bunch of useless wasters who have squandered our heritage.

I'm off to read your Ganges.

In 1916, a cuban art critic wrote about how great were the american comic strip artists as humorists, and about how ugly and esthetically despicable were those balloons "which seem to follow the characters" . He saw them as an intrusion in the image.

Now, you say, about the "the true narrative...", "The character was not "speaking" in a narrative sequence". I would say many of your pages are more discursive than narrative. The same with the mexican Rius books. They are long ramblings in "comics form".

Post a Comment