These'll be in "Famous Fictional" next Friday, Jan. 5. at Mad Art Gallery.

Some St. Louis artists were asked to do 2 "pieces" of the same size,

one of a fictional character (from books) and the other a cartoon character.

So in this profile of Milch he says:

So in this profile of Milch he says:"I try consciously to frustrate the impulse to think about a scene before I sit down to it, because--you know the highfalutin' expression 'You can't think your way to write action; you can only act your way to write thinking.'"

"You can't think your way to write action; you can only *think* your way to write thinking"and I thought this diagnosed flaws in my own fiction writing. Yeah, I thought, that's right: I tend to overthink my stories and my stories tend to be about thinking, not action. Gotta work on that.

"You can't think yourself into right action, you can only act yourself into right thinking."and I clearly hear "right" instead of "write" because of the context and it suddenly clicks. That makes more sense! (And I could suddenly connect it to Milch's interest in William James.)

"You can't read your way to right jack shit."

...Lastly, there’s Kevin Huizenga’s three stories about a character named Glenn Ganges, who lives with his wife Wendy in suburban Michigan. I love Kevin Huizenga’s work, although I think those aliens would have a fair amount of trouble deciphering it [refers to something earlier in the intro obvs]. He reminds me of a deadpan, slapstick, surreal, suburban Herge. These are magical stories. “The Curse” manages to conjure up deafening noise, acrid stench -- the two senses that you wouldn’t think a graphic artist could capture. “28th Street” is one of the best fairytale retellings I’ve ever read. The third story, about lost children, says more sensible things about pictures and narrative than I’ll ever manage. “You can’t help but try to form a story in your head,” the narrator, Glenn Ganges, tells us about the pictures of missing children on advertisement fliers. “It adds up and becomes like an accidental graphic novel, whose story is mostly hidden, though sprawling landscapes and tragic scenes are hinted at. Every week two new faces and you imagine the scenes in between.”

Like the fliers, which are full of imagined transformations, helpfully depicting children who have aged -- even while missing -- listing information about parents and locations, Huizenga’s panels are signposted with words and names. There are the suggestive, diminished names of stores -- there’s Eden’s, and Paradise Bagels -- and slogans on t-shirts, newspaper stories about Sudanese refugees, historical and observational data about starlings and suburban sprawl. There are wordless transformations, too. Pictures of the missing children suddenly lift into the sky and become a murmuration of starlings. A curvy suburban road branches off and in the next panel it’s a tree full of noisy bird -- starlings again. A Mega Mart is a President’s Palace, or possibly the entrance to the feathered ogre’s subterranean cave. Squirting gasoline from the pump straight into the eyes, rather than the tank, brings on visions that change a strip mall into a scene out of Hieronymus Bosch, with Lovecraftian beasties, Native American-style totem animals with wings and hooves and staring eyes, and even those uncanny ghosts from Ms. Pacman. The panels begin to seep and drip darkness, like a kind of smog out of which appear starlings, a moon like an enormous egg, and finally, the strangest thing of all: Eden’s, the Mega Mart.

Like the other two artist/writers in this anthology, Kevin Huizenga is writing about a quest, a journey. Along the way, the narrator discovers a styrofoam take-home container is an enchanted, battery-operated doggybag of plenty. A monster explodes with rage, and breaks into dozens, hundreds, thousands of starlings, all of them croaking curses (except for one, which says “cheep”. After all, they are in the basement of the Mega Mart.) The stories are crammed with other visual jokes and references, like the guy with a moustache in the advertisement on the back of a missing children flier, paid to appear “thrilled with modernistic carpet cleaning”. He looks familiar to Glenn. He looks familiar to us as well -- maybe he’s the neighbor, Karl, from down the street in one of the other stories, “Curses”, who recommends using a bottle rocket to get rid of the starlings. And of course, maybe getting your carpet cleaned will help locate a missing child, the way praying to Baal, or stealing a feather from the ogre will break the curse so that Glenn and Wendy can have a child of their own.

Meanwhile, while Glenn is fretting about the missing children, the Sudanese refugees -- the “lost boys” -- who have been brought to America, are lost again, right under Glenn’s nose. They’re trying to navigate their way through the suburban landscape. It isn’t easy. So why do you even bother?

It all comes back to whether or not Glenn and Wendy will manage to have a baby. In the end, will everyone’s problems be solved? Sure. The waitress, the gas station attendant, the Sudanese clerk at Eden’s, Glenn and Wendy, everyone gets a piece of what they need. But even when you’ve stolen the ogre’s feather to break a curse, and you’re all set to live happily ever after in the suburbs, there are still difficulties. When you break a curse, it just breaks into smaller pieces, after all. The new baby won’t stop crying, and all the starlings (little, black curses) have come home to roost in the trees in your yard. But, as the narrator reminds us, the starlings aren’t just a curse. It isn’t just noise. They sing. They’re performance artists. They can mimic cell phones, dogs barking, car alarms, Latin and Greek and Mozart: all the same kinds of things, both magical and decidedly unmagical, that an artist/writer can draw on. In “28th Street,” it’s a starling who gets to have the last word of the story -- “The End” -- but it’s Kevin Huizenga who set him to sing.

(I highly recommend her wonderful short stories, especially the title story of her collection Magic for Beginners. Many stories from that collection made a big impression on me and have really burrowed into my head.)

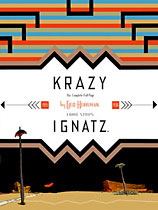

(I highly recommend her wonderful short stories, especially the title story of her collection Magic for Beginners. Many stories from that collection made a big impression on me and have really burrowed into my head.) From Bill Blackbeard's introduction to Krazy & Ignatz 1935-1936: "A Wild Warmth of Chromatic Gravy":

From Bill Blackbeard's introduction to Krazy & Ignatz 1935-1936: "A Wild Warmth of Chromatic Gravy":"There are just over four hundred and fifty of them, and each one a masterpiece of graphic comedy. The marvelous product of the last nine years of Garge's richly fruitful life, these weekly color Krazy Kat pages, stunning as they are, almost failed to physically survive the editorial and institutional rigors of their time. We are, in fact, damned lucky to have them on hand at all as source material for this series. There were, you see, just two newspapers -- six day a week sports and crime news afternoon newspapers, throwaway rubbish -- that printed virtually all of the color Kat pages from start to finish. Neither the New York Journal nor the Chicago American, sensational Hearst papers, had anyreferential status at all, and most libraries in their sales areas shunned them -- two papers that virtually no one of any artistic or literary taste and judgment ever saw fro mthe the strip's 1935 start to its 1944 conclusion. Two tombs for the foremost comic strip of all time.

Luckily there was a single dedicated comic strip buff, August Derleth of Sauk City Wisconsin, founder of Arkham House in 1939, who clipped and saved every color Kat page, donating his run to the Wisconsin State Historical Society..."

"...a man named Blackbeard told a reporter that he had a story for me...Blackbeard had a formal, slightly breathless way of talking; he was obviously intelligent, perhaps a little Ancient Marinerian in the way that lifelongcollectors can be...Some of what Blackbeard told me I couldn't quite comprehend: that the Library of Congress, [esp. arch-villain Verner Clapp, pictured left -kh.] the purported library of last resort, had replaced most of its enormous collection of late-nineteenth and twentieth-century newspapers with microfilm, and that research libraries where relying on what he called "fraudulent" scientific studies when they justified the discarding of books and newspapers on the basis of diagnosed states of acidity and embrittlement.

...In 1967, filled with an ambition to write a history of the American comic strip, he'd discovered that libraries were getting rid of their newspaper collections...Unfortunately he was a private citizen--the library's charter permitted the transfer of material only to a non-profit organization. "I became a non-profit organization so fast you couldn't believe it," Blackbeard told me...He went around the country picking up newspaper volumes..."